Surgery: Setback or Motivation?

Today, Topo Ambassador Nick Tsotsu is sharing with how he took his shoulder surgery, and what could’ve been a major setback, and turned it into motivation to run (and win!) a 50k race.

It’s May 8, 2021. I’m at a collegiate track meet with one last thing to do: run a PR in the 5k. Twelve and half laps later I had a new PR of 15:11.99. I was glad, but a little sad. I was in the best shape of my life, but in 3 days’ time, I would be undergoing shoulder surgery.

I have never been one to take time off from running for no reason. If I am totally honest, part of me is afraid to take time off. I have been racing at my peak fitness for a decade, and at the age of 35, I fear that if I get out of shape, I will never be able to return to this level of fitness. But my shoulder had gotten bad. On two separate occasions, I dislocated my shoulder just by sneezing. And the longer I put the surgery off, the less complete my recovery would be.

I decided it was time to fix my shoulder, even if it meant no running for 6 weeks. Rather than view this as a setback, I looked at it as new challenge. Could I get back to this level of fitness, and if so, how quickly?

I set a process goal I knew would be challenging: get on the stationary bike for a full hour every day for 6 weeks. I set a performance goal that seemed nearly impossible: win the Spartan Monterey 50k on August 22, about 15 weeks after my surgery. That would give me 9 weeks of running to prepare for a 50k with 8000 ft. of climbing. I had only ever run one 50k before, so this would be quite the challenge indeed. The surgery went well, and I got on the stationary bike the very next day.

I do not enjoy cycling the way I enjoy running, and the stationary bike is worse than the treadmill. I was ready for the boredom, but I was not ready for how uncomfortable I would get. I would be dripping sweat after about 10 minutes, awkward with only one arm on the handlebars, and my shoulder kind of hurt. I can’t tell you how badly I wanted to quit early some days, but each day, I made the full hour. If I got on the bike every day and was still not able to win the 50k, at least I would have felt like I gave it an honest effort. Even when my wife and I went on a trip, I made her pack up the bike and trainer. I wasn’t allowed to lift anything with my arm, so she had to set it up for me at each place we stayed. I know she might not really understand why it was so important to me, but she understood that it was; I couldn’t have done it without her support.

After 4 weeks, I talked my physical therapist into allowing me to run slowly while wearing the sling. And just like that, the comeback began. I started out slowly, just 20 minutes every otherday at first and even that was a struggle. During my 6th week after surgery, I managed 21 miles of running. I began weaning myself off the sling during the 7th week. To test my progress, I ran a 1600m time trial and managed about 4 seconds faster than my 5k race pace before surgery. I did my first 10 miler in my 8th week. In my 9th week, I managed 48 miles and included a 20-minute tempo run. In my 10th week, I was right back to around 5:20 pace for my tempo work and I accidentally ended up running over 63 miles. Reading this, you probably don’t get a sense for how long all of this felt. Every day I wanted to run more than I should and every day I had to temper my enthusiasm, be patient, and listen to my body.

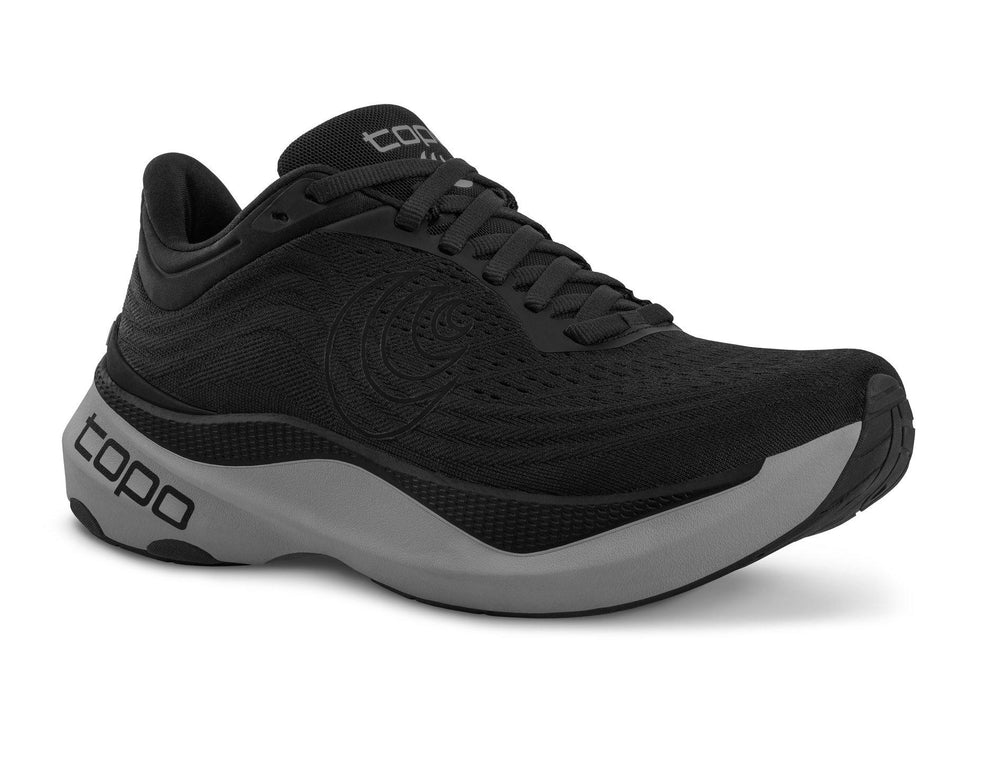

I signed up for a local 5k (the Brazen Summer Breeze 5k), for which I owned the course record. In the past I had won it easily, but I didn’t want to let my guard down, so I wore my trusty Topo ST-2s because you never know who might show up to a local 5k. As it turned out, Ethan Ashby of the Pomona-Pitzer NCAA DIII cross-country national champion team decided to show up on race day.

I took out right behind Ethan and took the lead before we reached the end of the first mile. Over the second mile I opened up a 5-second gap that I was able to hold to the finish. I crossed the line in 16:09, taking my first win in months and shaving 2 seconds off my own course record in the process. With my confidence firmly boosted, I was ready for the big test at the Monterey Spartan 50k. Even if I couldn’t win the 50k, I was extremely proud of how I was handling my surgery, my cross-training, and my return to form.

In my first 50k, I made all the rookie mistakes: I took out too fast, I got lost and dehydrated, I cramped up, I had a miserable experience and finished in a disappointing 3rd place. This second one would be different. I was well-prepared, my Ultraventure 2’s had less than 50 miles on them, and I decided I would take out extra conservatively and eat more food than I thought I would possibly need.

I found myself alone in the lead before the end of the first mile and out of sight of anyone else about 2 miles in. I felt good. I was cruising over the hilly course and getting really excited about achieving my goal, right up until about 23 miles in. Then my legs started to rebel. My calves started cramping badly.

Now I was scared. I wanted the win so badly. For months, it was my primary focus. All those hours on the bicycle, all those runs while wearing a sling. I had been dreaming about winning this race, writing the story of my comeback in my head. Now I was so close, I had worked so hard, but my body was giving out and my legs were threatening to ruin the ending to that story. I had no idea how much of a lead I had, but I knew I could lose that in a couple of miles if I had to walk, so I ran. I ran whenever

Now I was scared. I wanted the win so badly. For months, it was my primary focus. All those hours on the bicycle, all those runs while wearing a sling. I had been dreaming about winning this race, writing the story of my comeback in my head. Now I was so close, I had worked so hard, but my body was giving out and my legs were threatening to ruin the ending to that story. I had no idea how much of a lead I had, but I knew I could lose that in a couple of miles if I had to walk, so I ran. I ran wheneverI was able to. I worked my way to the finish line as fast as I could. Gradually, painfully, and one step at a time.

When I crossed the line, I let out a yell of victory. In that yell, I finally released the months of pain, discomfort, and struggle. I released the fear of not regaining my fitness, the anxiety and uncertainty, and the difficulty of the last 4.5 hours. At the same time, I tried to take in all the joy of achieving my goal. Tears filled my eyes as I thought about all I had gone through over the past few months, how proud I was of my efforts, and how lucky I was to be able to do all these amazing things I love to do. As it turned out, I didn’t need to worry so much about getting caught. It would be another hour and 21 minutes before another athlete would cross the finish line.

Like all things in running, it was the journey that really mattered. It was thinking about the journey that brought the tears to my eyes. It

was the journey that changed me and my perception of what I could achieve. I set ambitious goals that required more discipline and hard work than any goals I had ever set. Achieving those goals gave me an enormous sense of satisfaction. Somehow, I managed to take a potentially disastrous situation and turn it into one of the greatest experiences of my life. Through this experience, I realized that difficult situations can either motivate you or demoralize you, but you have a say in which. Throughout your running career (and life), you will undoubtedly encounter such situations. Choose wisely!